Projects you can do with a Star Analyser

On the page below, you’ll see examples of the kinds of exciting projects you can do with our 1-1/4″ Star Analyser grating.

With a few clicks in our RSpec software, you can convert an image you captured with a Star Analyser grating into scientific data like you’ll see below.

If you have questions about these projects, you can email us via our contact form (link) or post questions on our forum (link).

Watch the video below to see some of the exciting projects that you can do with a Star Analyser and small telescope:

Take a moment to watch this video to see what’s possible with Star Analyser

A Personal Message from Tom Field, the creator of RSpec

I want to make a confession here. When I first started doing spectroscopy almost ten years ago, I didn’t know a lot of the science that you’ll see on this page. I was a visual observer and imager. But, I didn’t know much about the science behind what I was seiing.

When I began to capture spectra, I made an exciting discovery: when you capture data yourself, it has added meaning. You care about it. You want to know more. You go out and look things up on Wikipedia. You begin reading books on the topic. And, you understand and remember more of what you’re reading because it describes data that you’ve captured yourself.

For me, spectroscopy has opened up a much deeper dimension to all of my observing. It can do the same thing for you! Have questions? Get answers from me via a live tech support chat or contact form: link.

Identify star types (OBAFGKM)

You can use a telescope as small as 4″ or even just a DSLR to capture a collection of spectra of stars of different temperatures. When you compare the spectra to one another, you can spot differences in the absorption lines as shown below.

You can also determine each star’s approximate temperature and type by comparing their spectra to those in a Reference Library in our software. And, RSpec comes with a complete set of videos that walk you through this process, step by step.

The image below is a collage of spectra that were captured with a Star Analyser grating, an 8″ Newtonian, and just an astronomical video camera. If you have a FITS camera and at least a 4″ telescope, you can easily capture this kind of data and much more! You can even do this with just a standalone DSLR on a tracking mount.

Please be sure to watch the video further up the page where the collage below is more fully discussed.

Each row in the collage is a different star. The hottest stars are at the top. The coolest stars are at the bottom. Notice, for example, that the cooler stars near the bottom have some broad dark absorption bands in the red end of the spectrum. Those are caused by the molecules on that star that weren’t burnt up because the surface temperature of these stars is relatively cool.

Also notice below, for example, that the Hydrogen Balmer (beta) absorption line in the blue (at 4861 Angstroms) is the strongest (darkest) for the Type A star that is 3 rows down from the top. This dark gap isn’t even visible in cooler stars at the very bottom of the table.

See? There’s a lot we can learn from such easy-to-capture data. And if it’s data you captured yourself, you’ll be amazed at how much easier it is to learn and remember!

Detect the emission lines on an emission nebula

Detect the spectrum of a supergiant star

Study star temperature and structure

Detect the methane atmosphere of Neptune or Uranus

The deep absorption lines are the Methane on Uranus.

Credit: Bogdan Borz (link) with 4-1-2″ refractor and ZWO video camera.

For an interesting discussion of the storms on Uranus, see link.

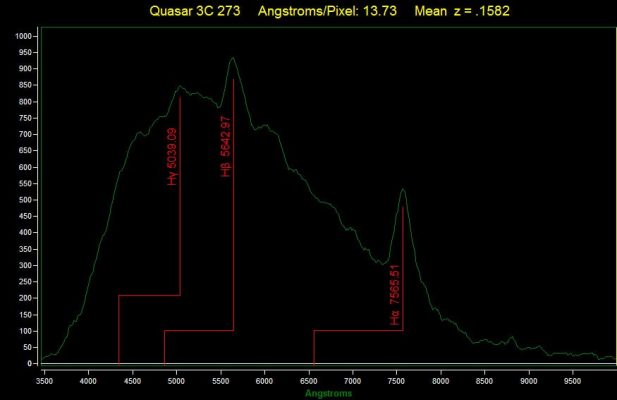

Detect the redshift of a quasar 2 billion light-years away

Below is the spectrum of quasar QSO 3C 273. It shows the redshift due to cosmological expansion.

Many amateurs have captured this spectrum on 8″ telescopes with less than 15 minutes of integration time.

Recommendation from Tom:

“There’s a wonderful interview with Maarten Schmidt, the discoverer of this first quasar. It’s exciting and fun to read such a personal account by a world-known professional. Read it here: link.

He describes in simple terms how he made his discovery and his persistence, fear, self-doubts, jubilation, working with colleagues, and the celebration on the night of the discovery.”

Also, here’s another site with information about quasar spectra with a Star Analyser: link.

The red shift of a quasar that is 2 billion light years away.

Credit: William Wiethoff

Spot the glowing dust ring around a star

The glowing disk around a star.

Credit: Johannes Clausen

Measure the redshift of galaxies with a Star Analyser

The image below shows the spectrum of Seyfert Galaxy UGC 545, a mag 14.1 galaxy with an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN).

The high luminosity of this galaxy’s core makes it visible despite being at a significant distance from us. And the compact, almost stellar appearance allows our Star Analyser diffraction grating to be used. Not all galaxies are suitable for this measurement with a Star Analyser.

The red shift of a distant galaxy shows the expanding universe.

Credit: Robin Leadbeater with 8″ telescope and webcam (link)

Detect the stellar winds of a Wolf-Rayet star

The characteristic emission lines are formed in the extended and dense high-velocity wind region enveloping the very hot stellar photosphere. This produces a flood of UV radiation that causes fluorescence in the line-forming wind region. This ejection process uncovers in succession, first the nitrogen-rich products of CNO cycle burning of hydrogen (WN stars), and later the carbon-rich layer due to He burning (WC & WO stars). Most of these stars are believed finally to progress to become supernovae of Type Ib or Type Ic.” (Credit: Wikipedia link)Yes, it doesn’t take a ton of gear, skill, or dark skies to capture fascinating spectra like this one! It’s images like this that we find so enormously exciting.

The carbon emission near the hot core of a Wolf Rayet star

Credit: Janet Simpson, Canon DSLR, 85 mm lens, 30 second exposure with tracking mount

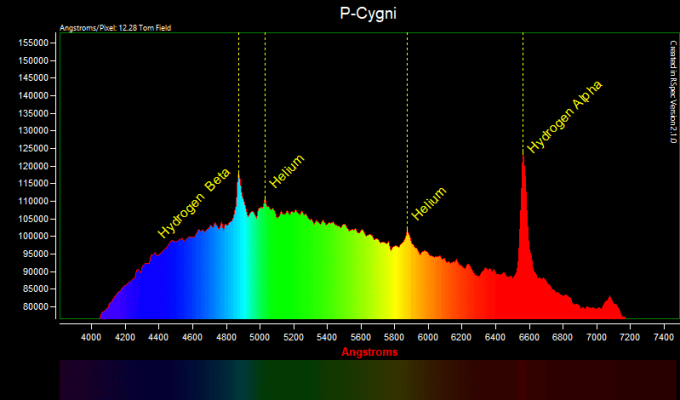

P Cygni emission lines

P Cygni is a blue supergiant and is one of the most luminous stars in our galaxy.

Emission lines due to hydrogen and helium can be seen in the image below. The characteristic P-Cyg blue-shifted absorption bands can not be seen at this low dispersion. (A dispersion at least 5x greater would be needed.) .

P Cygni star showing emission lines from surrounding gas

Credit: Robin Leadbeater using a webcam, his VC 200L, and a Star Analyser (link)

Capturing a low resolution spectrum of the Sun

Using a sewing needle to capture a solar spectrum

The above spectrum, when processed in RSpec, clearly shows the Sun’s Fraunhofer lines, as seen in the image below:

The Sun’s Fraunhofer lines

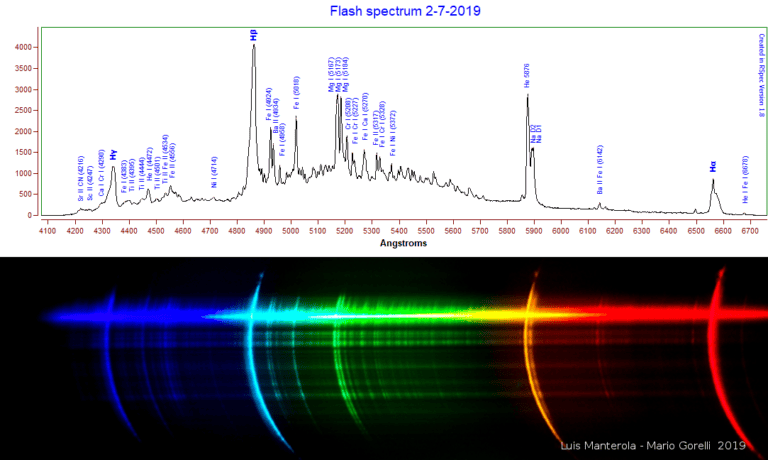

Eclipse flash spectra

The flash spectrum of the Sun. (Click to enlarge.)

Changes in a variable LL Lyr star

The temperature and the Hydrogen Balmer lines changing on an RR Lyr star.

Credit: Umberto Sollecchia in Italy with a 110mm refractor and a Star Analyser grating.

The spectrum of a comet

The comet spectrum below clearly shows the green emission from glowing Carbon (the so-called “Swan bands” – Wikipedia link)

A glowing comet! Credit: Vikrant Kumar Agnihotri,

High-resolution details of a comet's composition

This is a detailed spectrum of a comet captured with a slit spectrometer. Notice the variety of complex molecules. These complex molecules are thought to have provided the raw material that formed the building blocks of life when they pelted the Earth during its early history.

The details of a comet. Credit: Rainer Ehlert

Identifying a supernova

Below is a beautiful spectrum of a supernova captured by David Strange in the UK. The deep absorption is the “fingerprint” for a Type Ia supernova. At the time he took this image and created the profile, David had been using RSpec for just over a week.

Newcomers are often amazed at how little integration time is needed to capture spectra. This spectrum was captured on a 9″ SCT, with only 30 twenty-five-second images. You don’t need a mountaintop observatory, a large telescope, or hours of integration time. Dark sky sites aren’t required. Spectroscopy is much less affected by urban light pollution than visual imaging.

Supernova spectrum shows the fingerprint of a Type Ia

Here’s the original FITS image that was used to create the above profile: link. Here is a video that discusses how to calibrate the spectrum: link.

Here’s the paper by Filippenko and Reiss on using Type Ia supernovae as evidence for an accelerating universe: link. The article is quite technical, but it shows how professionals use supernova spectra like the one above..

Measuring how fast a supernova's shell is expanding

Once you have captured a supernova spectrum like the one above, it’s easy to calculate how fast its shell is approaching us. We can determine its blue shift with just one multiplication, one division, and one subtraction.

Observe the changes to a supernova's exploding shell over a few weeks

Below is a series of spectra taken of a supernova during the three weeks immediately following the explosion. These were taken with just a 4″ refractor.

This report was published in Sky & Telescope Magazine. Here’s the PDF: link.

A supernova’s shell expansion slows down over 3 weeks.

Click to enlarge

Measuring the spectrum of a nova

Below is the spectrum of Nova Del 2013. Alfred Tan captured this image in Singapore, using his 90 mm Williams Optics APO and an astronomical video camera. The Hydrogen emission lines are very clear and typical for this type of nova.

The clear Hydrogen emission lines of a nova.

Studying how a nova changes

Below is a poster that was presented at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. Using a Star Analyser grating and RSpec, a team at the University of Minnesota captured 44 spectra of Nova Delphini 2013 over four months. Major phases of the nova evolution can readily be identified. Here’s the PDF of the full poster: link.

Carbon stars - red giants!

Below is an impressive image showing the C2 Swan bands on several Carbon stars. Notice how much stronger the signal is in the cooler, right-hand, red end of the spectrum. Read more about Carbon stars at this Wikipedia link.

The spectra of red giant stars. Click to enlarge.

Credit: Torsten Hansen, with a 20 cm (8″) telescope,

Star Analyser grating, and an astronomical video camera.

Advanced studies in star evolution

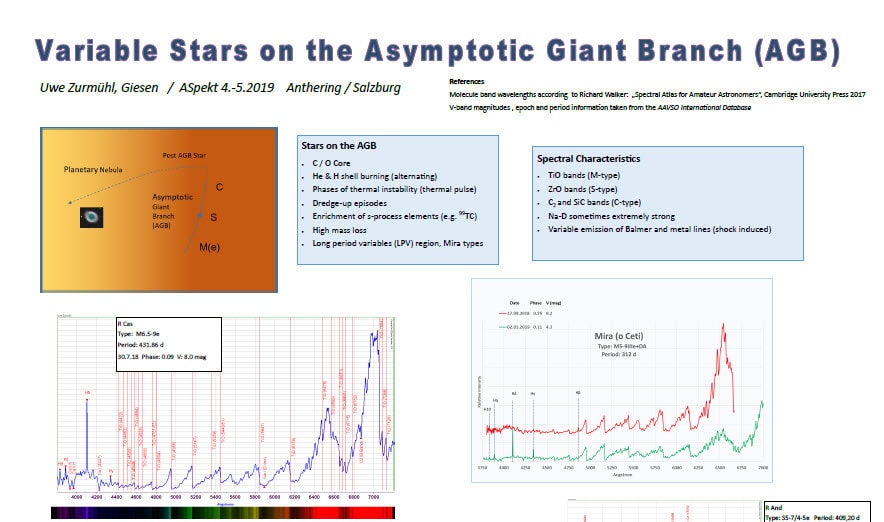

RSpec user Uwe Zurmühl presented his findings on variable stars in the AGB branch at a recent conference on variable stars. This is exciting science being done by an amateur astronomer using a Star Analyser. The report is quite technical.

Uwe Zurmühl’s paper on variable stars on the AGB branch.

Full PDF: link.

Observing plan

Here’s a great spectroscopy observing plan by an RSpec user: link. You’ll see a wide, wide range of exciting spectra. As you capture spectra of these objects, read up on each of them (starting with the Wikipedia entries). You’ll be building a foundation of knowledge that will astonish you.

Spectra Library of Constellations

Star Analyser user Tony H. has built a library containing the spectra of stars, constellation by constellation. He did this as a personal learning project. Each star spectrum is accompanied by a brief discussion of the results. He also describes the equipment and procedures he used when collecting his data.

Tony has generously made the library available to us all. His observations and results are interesting and show the range spectra that you might capture with a small telescope. Download his library PDF here: link.

Questions or comments about the library can be directed to [email protected].

GRISM: Using a Star Analyser grating with a prism

Uwe Zurmühl has done some helpful research on how to best use a Star Analyser grating with a Star Analyser prism ($119, link).

The combination of these two is called a GRISM and can improve the resolution of a standalone Star Analyser.

Uwe’s results were published in Spektrum, Journal of the Section Spectroscopy of the Society of German Amateur Astronomers. See pages 10 – 18 in this PDF: link.

For more information on the optical properties of a GRISM, see this YouTube video: link.

Also see this forum post that discusses the pluses and minuses of using a GRISM: link.